Knowledge Transfer: The Key to Developing the Next Generation of Leaders

The construction industry has always had a reputation for bringing people up through the “school of hard knocks,” where knowledge transfer occurred through a combination of taking on the most difficult jobs, doing whatever the boss demanded, and receiving a good butt-chewing when you screwed up.

The Backstory

I remember vividly one of the best butt-chewings I ever heard. The construction workday began at 7 a.m. but every morning, a young and newly hired laborer would arrive 5-10 minutes late for work. After a few days of late arrivals, the superintendent, in front of the rest of the crew, humiliated this laborer. In a booming voice, he told him he was an embarrassment to the job, he needed to get his butt out of bed and get to work on time, and if late one more day, he would be fired in front of everyone on site.

In full disclosure, that young laborer was me. While on summer break from college, I was working on a concrete crew. Given that I was spending my evenings out and about, I couldn’t seem to make it on to the job by 7 a.m., hence the very public and one-sided conversation with my superintendent. But this is not the end of the story.

About an hour after that embarrassing dress-down, the superintendent pulled me aside. He told me that my start time on the job was now 6:30 a.m. Upon arrival, I was to set out tools, unroll extension cords, prepare equipment, basically get everything ready for the rest of the crew. What this superintendent knew is that even if I arrived five minutes late for my new start time, I would still arrive 25 minutes before the crew’s start time – before anyone else arrived, meaning any tardiness would not be noticed. This tactic worked, and I kept my job that summer. It’s also a leadership lesson I’ve never forgotten.

Comprehensive Approach to Knowledge Transfer

Training in construction is much different today than it was 40 years ago when I began my career. Certainly, apprenticeship programs existed, but much of what we learned, whether in the field or in the office, was a result of a senior person taking the time and effort to show us how to perform a task or solve a problem. Today, the construction industry offers more formalized training programs.

In the field, safety training is dominant, while formal training ranging from the proper use of equipment to performing specific tasks is common. For office-based personnel, there are formal training programs in policies and procedures, new technologies, legal and risk mitigation, and human resources. Each of these formal training programs continues to improve our companies and our industry.

But what about the type of training that I learned from that superintendent over 40 years ago – training not found in a manual or a video, but that can shape an organization and its people? How do we best discover and implement that type of training and knowledge transfer in our companies?

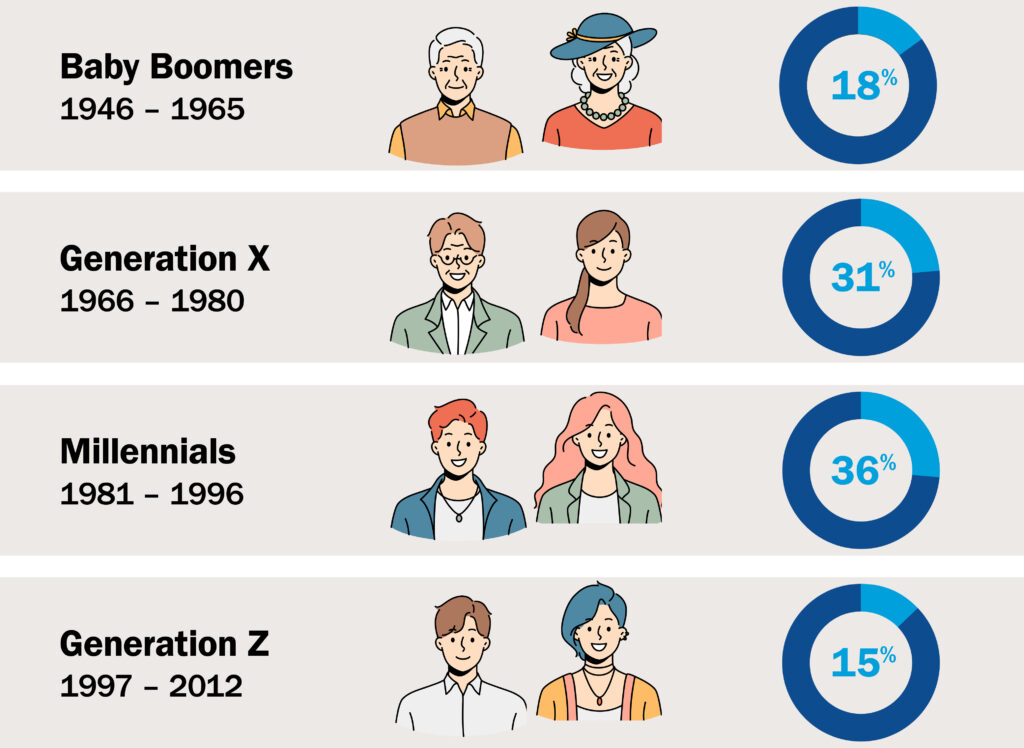

It is well documented that today’s workforce represents the greatest generational diversity of any time in history. People are now living and working longer, and the generational lines have become blurred. The 70-year-old routinely works alongside a 25-year-old, with both reporting to a 40-year-old. It will be interesting to see the future impact this will have on our industry, but I believe there is an opportunity for companies to embrace this new dynamic, both for the good of the industry and the good of their organizations.

Knowledge transfer refers to a process in which seasoned veterans share their skills, information, experience, and ideas with a company’s younger and less-experienced workforce.

Older workers have a wealth of resources living in their memory banks, fueled by past experiences. These seasoned veterans have learned from a lifetime of achievements and mistakes. They have been a member of both highly successful and horribly failed teams, witnessed both cultural growth and erosion at a company, experienced ethical situations that had far-reaching implications, and have worked alongside both great and poor leaders. These employees have impactful stories to share and valuable lessons to teach.

However, individuals who possess this knowledge may be reluctant or uncertain how to best share their stories. Therefore, if a company wants to unlock an individual’s lifetime of knowledge and experience, it will need to invest in the process of understanding the experience of their seasoned veterans, then determine how to best disseminate that knowledge throughout the company. I believe there are two opportunities for an organization to harness these experiences and translate them for the younger generation.

Options for a Knowledge Transfer Plan

1. The first opportunity is to develop a training forum utilizing seasoned employees as trainers, where they are provided a setting and opportunity to pass down wisdom and experience gained over a career. Subject matter should be purposefully developed, and guidance will be necessary to ensure that such a program is properly executed. But a program such as this can utilize older employees as an in-house training resource to address topics including culture, ethics, problem solving, and specific management skills.

Whether done in a formal or informal manner, the goal is to give seasoned employees a forum to stand in front of a group of individuals and share a story, an anecdote, a past experience, or a level of knowledge that can benefit those in the audience.

2. The second opportunity is the development of an individually focused mentoring program. Whether implemented as formal or informal, a mentoring program will provide young managers with the opportunity to meet with senior employees and discuss topics including career development, workplace behaviors, situational responses, and work/life balance. It also provides a resource to seek answers or advice relating to a specific problem or a major decision.

A mentoring program further creates an attitude of empathy and caring among employees and within a company, which in turn has shown to increase workplace behaviors and performance.

Conclusion

Both of these programs will require a level of commitment and investment of time and resources, but I would argue they are worth the investment. Looking back on my career, I now realize some of the greatest lessons I learned that have contributed to my success were the result of being exposed to the wisdom and teaching of seasoned veterans. They cared about teaching me and making sure I was smarter at the end of the day than at the beginning. They provided me with opportunities to understand a situation, taught me how to solve a problem, or made sure I learned an important lesson, always in a purposeful and intentional manner, and with an attitude of empathy and improvement.

I witnessed this 40 years ago when an older superintendent treated me as a person, and not just another tool on a jobsite. He saw that I worked hard, used intelligence in my work, and had a passion for construction. He also saw that I had a flaw that was inexcusable on a construction jobsite. He found a way to address my flaw, while saving face for both of us. If he had fired me, it would have been impactful, maybe to the point where I considered giving up on my construction career. Instead, I now have a great story to tell future leaders.

Seasoned veterans within a company may be that company’s greatest resource. The companies that understand this, and then create an environment where the wisdom, experience, and knowledge of these individuals is passed down to their younger employees in a purposeful manner, will be the most successful over time.

About the Author – Brian King, FDBIA, is the Founder and CEO of A M King, an integrated Design-Build firm headquartered in Charlotte that provides multiple services required of highly complex facilities in niche markets throughout the United States.