Taking a Close Look at the Economic Situation: September 2023

With the arrival of September, football season and just three months to go before 2023’s books close, football fans are wondering which college teams in the reshuffling conferences will make it to the top 10, and recession watchers, looking at tea leaves and listening to Fed-speak, are trying to determine when and if the long-expected economic slowdown will show up. Both groups are focusing on teams and economic agents trying to find a new equilibrium. Most likely, the economic forecasters will do no better than their football counterparts, but here’s what we know right now.

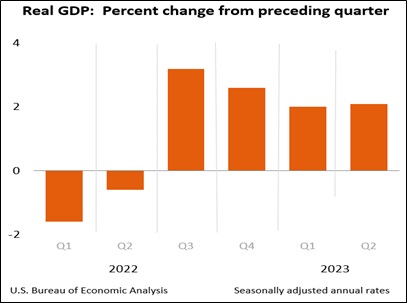

The economic outlook turned more optimistic when the Commerce Department’s first-quarter estimate of 1.3 percent real GDP growth was revised upward significantly in June to 2.0 percent.[1] Then, in late July, the department’s first estimate for 2023’s second-quarter real GDP growth came in at a healthy 2.4 percent.[2] But long about the end of August, Commerce revised the number down to 2.0 percent.[3] While surely not hot, two percent growth is solid. (See the nearby chart.) There’s not a sniff of recession in those numbers. But let’s dig a bit deeper.

Recent data on falling temporary worker hires and slower new job openings, don’t look so good.[4] They and the new high 7.0% mortgage rate, which will take a bite out of housing starts as well as a plug from spendable personal income when mortgage payments rise automatically for indebted homeowners, portend a slowing 2024 economy. And that is just what a number of forecasters are saying. For example, the Philadelphia Fed panel of forecasters and Wells Fargo economists have raised slightly their 2023 real GDP growth forecast and reduced their forecast for 2024.[5] No, they are not showing meaningful negative numbers, but close to negative.

Data for the overall economy seem to be saying that large expenditures of federal government transfers under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Chips and infrastructure legislation are bringing increasing industrial and civil construction activity just at the time when the economy was tending to slow significantly. For example, powerful tax and other incentives associated with building electric autos and batteries on U.S. soil have led to the start or planned construction of 30 battery plants.[6] Among these are South Carolina factories in Florence, Charleston and Woodruff, a North Carolina plant in Liberty, and Georgia plants in Bartow County, Commerce, and Savannah. There are also over $700 billion planned expenditures for transportation and water resources projects across the nation.[7] These large expansions mean that we are made better off in the short run, but paying interest on the increase in federal debt, let alone paying it off, may put a major pinch in the budgets of future generations.

A recent Manhattan Institute report puts some dimensions on the large growth in government debt that must be dealt with: “In 2007, the government owed $8.6 trillion in today’s dollars. As of the end of 2022, it owed more than triple that, $26.9 trillion, including $4.8 trillion in pandemic-era borrowing.”[8] Now, with higher interest rates and an exploding level of federal debt, the annual interest cost of the debt, some $644 billion this fiscal year, is about equal to the annual $692 billion defense budget. In a few words, given the debt and revenue picture, we can be certain that something in the federal budget will have to yield.

But future generations and today’s taxpayers may not be the only ones who should be concerned. In spite of the current low unemployment rate and strong retail sales, leaders of U.S. small businesses checked by the National Federation of Independent Businesses are not optimistic about the current year’s outlook.[9] They and leaders of U.S. major corporations surveyed by the Business Round Table are worried about inflation, the inability to find workers, and Washington gridlock that seems to make it impossible to take meaningful action on immigration control and deficit spending.[10] Add to this the strongly negative readings registered in the most recent University of Michigan consumer confidence survey and we get a decidedly strong picture that things economic are generally out of balance.[11] And that makes forecasting when and if the next recession comes in the next 12 months all the more challenging. As for me, I expect we will see negative growth in the real GDP during 2024’s first half.

What about Home Region?

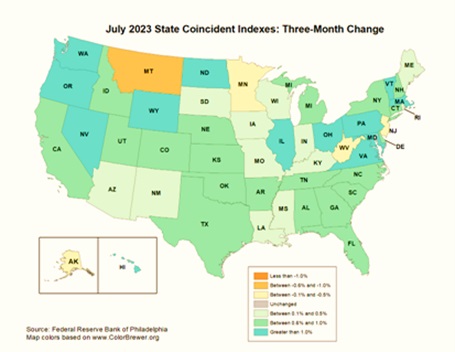

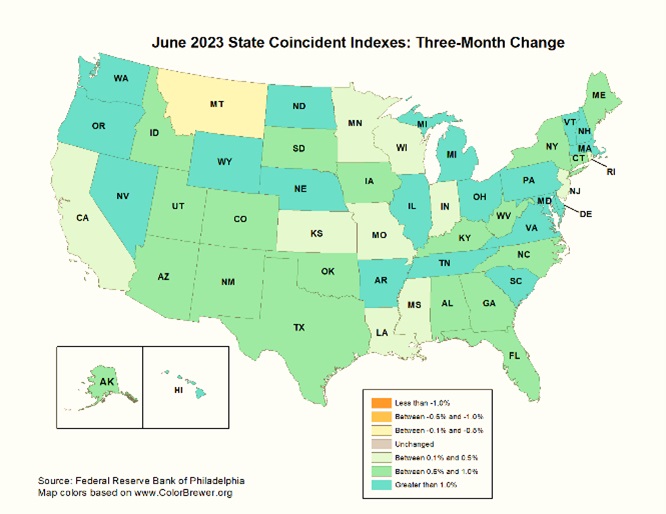

Turning to our region, we continue to see a positive picture. Nearby, I show state outline maps of current economic indicators produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia for the most recent two months.[12] Looking closely, one can see some weakness showing up in July as compared to June’s data. Note that South Carolina is a bit weaker in the July map and that there is an overall reduction in the number of brighter blue—stronger growth—states. We can also see that the July map contains three yellow or tan states—Michigan, Montana, and West Virginia. These are experiencing weak to negative growth in the coincident economic indicator.

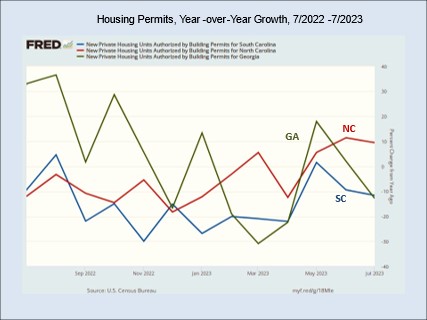

We get another indication of economic outlook for states in the region when we examine year-over-year growth in housing permits issued for the most recent twelve-month period. In the nearby chart, we see housing permit growth rates are declining for each of the three states in the region.

Final Thoughts

The data and the world situation tell us that the U.S. and world economies are out of balance and in the process of finding a new equilibrium. Relative to most of the developed world, the U.S. economy is doing rather well, but higher interest rates and other forces at play paint a darker picture for the next 12 months. As of now, based on federal policy actions already taken, we should expect 2024 to bring lower inflation, perhaps 2.0% or lower, close to zero real GDP growth, and, if we are fortunate, a political coming to grips with our ever-expanding debt. Of course, our region’s prospects are tied to those of the larger world, but at the same time, the positive forces of exceptional growth in population and investment continue to give the area a favorable nudge.

Dr. Bruce Yandle is Alumni Distinguished Professor of Economics Emeritus, Clemson University.

Sources

[1] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product (Third Estimate), Corporate Profits (Revised Estimate), and GDP by Industry, First Quarter 2023,” June 29, 2023, https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/gdp1q23_3rd.pdf.

[2] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product, Second Quarter 2023 (Advance Estimate),” July 27, 2023, https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/gdp2q23_adv.pdf.

[4] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL and https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?graph_id=1145937&rn=324.

[5] Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, “Second Quarter 2023 Survey of Professional Forecasters,” May 12, 2023, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/surveys-and-data/real-time-data-research/spf-q2-2023.

[8] https://www.city-journal.org/article/the-permanent-crisis-economy.

[9] https://www.nfib.com/surveys/small-business-economic-trends/

[10] https://www.businessroundtable.org/media/ceo-economic-outlook-index

[11] https://www.sca.isr.umich.edu/ and Wells Fargo, “Weekly Economic & Financial Commentary,” July 21, 2023, https://wellsfargo.bluematrix.com/links2/html/c6713751-aaa4-47d0-9b94-b78583d765a8.

[12] https://www.philadelphiafed.org/surveys-and-data/regional-economic-analysis/state-coincident-indexes.